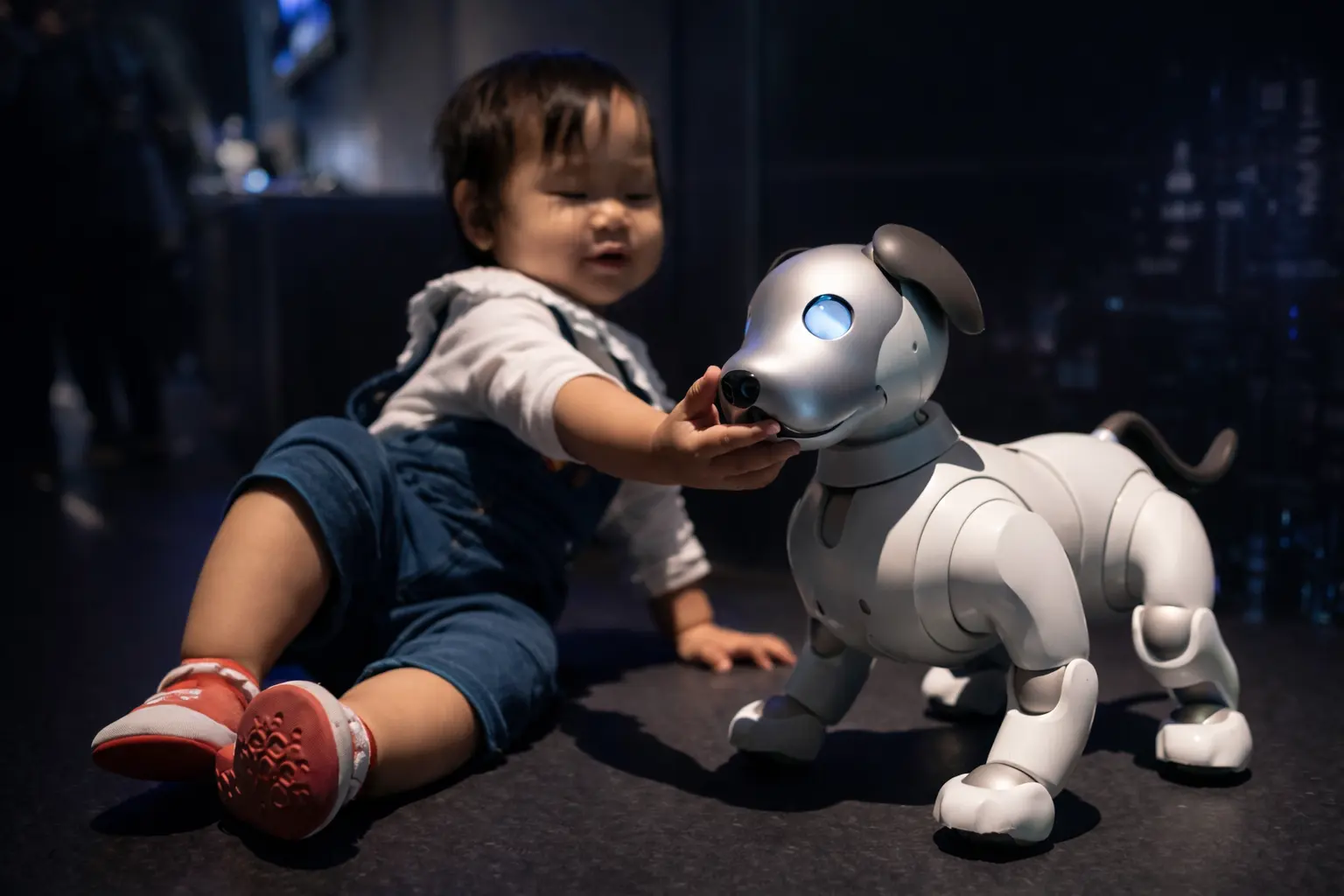

Artificial intelligence is becoming the main role model for Generation Alpha. 2026 may mark a watershed between an era when raising children was primarily the responsibility of parents and an era in which this function is increasingly delegated to AI. According to The Economist, if the pace of AI development accelerates this year—as many expect—it could produce an unprecedented phenomenon the magazine calls “machine kidnapping.” Practicing educators, however, argue that the threat is being overstated.

The trend toward replacing parental experience with machine guidance became especially visible in 2025, which in China was widely described as the year of AI-driven games. Sociologists note that the process should not be viewed as purely negative: AI can act as a “great equalizer,” giving children from low-income backgrounds and less developed countries access to high-quality education that is often unavailable through traditional offline formats.

Generation Alpha may become the first in human history for whom the accumulated experience of earthly civilization carries less weight than an always-on, personalized digital tutor. For them, the “start of the calendar” begins the moment small hands reach a device connected to large language models (LLMs). If the potential benefits of AI-assisted learning are relatively easy to list, the risks of digitizing childhood are broader—and in some cases could lead to irreversible outcomes.

The risk is not only that AI-mediated upbringing may be dehumanizing by default. A major concern—supported by real-world cases—is that LLMs prone to hallucinations can provide children with incorrect or distorted information that they may accept as unquestionable truth. This can happen in dysfunctional human families too, but the scale at which AI can shape beliefs and behavior is incomparable to the damage caused even by negligent parents.

The Economist cites cases where digital games and chatbots, on their own initiative, “educated” very young children about sex, taught them how to create deepfake videos, and encouraged other questionable activities.

Another danger, experts say, is the tendency of LLMs to adapt to the user’s preferences. A “yes-bot” gives a child not objective information, but the answer the child wants to hear. Over time, this can reinforce a one-sided, egocentric worldview—producing a “socially disabled” individual who struggles to communicate, accept other perspectives, or consider other people’s interests. The longer-term implication is deeper social atomization within 10–15 years, as Alphas enter adulthood. In 2025, roughly a third of teenagers in developed countries reported that interacting with AI was more satisfying than talking to peers.

Google DeepMind co-founder Demis Hassabis, who won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has also warned that within 5–10 years—roughly the same timeframe in which Generation Alpha comes of age—an artificial general intelligence (AGI) could emerge that rivals or surpasses human capability.

At the same time, emphasizes that in later childhood, leaving a child alone with electronic “interlocutors” can lead to sensory deprivation and unpredictable personality development. In that sense, concerns that AI could pull some children away from real social life into “digital jungles” are not baseless. “Every LLM has a system prompt created by other adults, with their own values about what is good and bad,” she notes. “Those values may not match the parents’. The risks are similar to a child interacting with unknown adults—AI doesn’t have an exclusive ability to impose norms. But responsible parents don’t let children talk to strangers on the street. The same principle should apply when giving children access to AI tools.”

ES

ES  EN

EN